It’s been a wonderful August. Having returned from some exceptional soaring out west while on my honeymoon, I was not expecting much from Blairstown. This time of the year tends to yield hot, hazy, and humid conditions. The kind where you can hardly see more than several miles away at several thousand feet. When you spend all day circling while the variometer occasionally beeps to remind you it is still on. When you yawn and start falling asleep as you keep going round and round in a thermal, to get high enough to make a several minute glide, to repeat the process all over again. Should you venture away from the airport, it is the frequent excitement of looking for airports and fields to land in that keeps you awake.

Not this August. Upon my arrival, I learned that the northeast has been enduring the longest sustained drought in two decades. The poor farmers… and the grinning glider pilots! Cool nights followed by hot and dry days set up long soaring days with high thermals, at times exceeding 9000ft. It was like the club awoke from a long slumber and pilots starting flying every chance they could. Make hay when the sun shines, at least if you’re a soaring pilot!

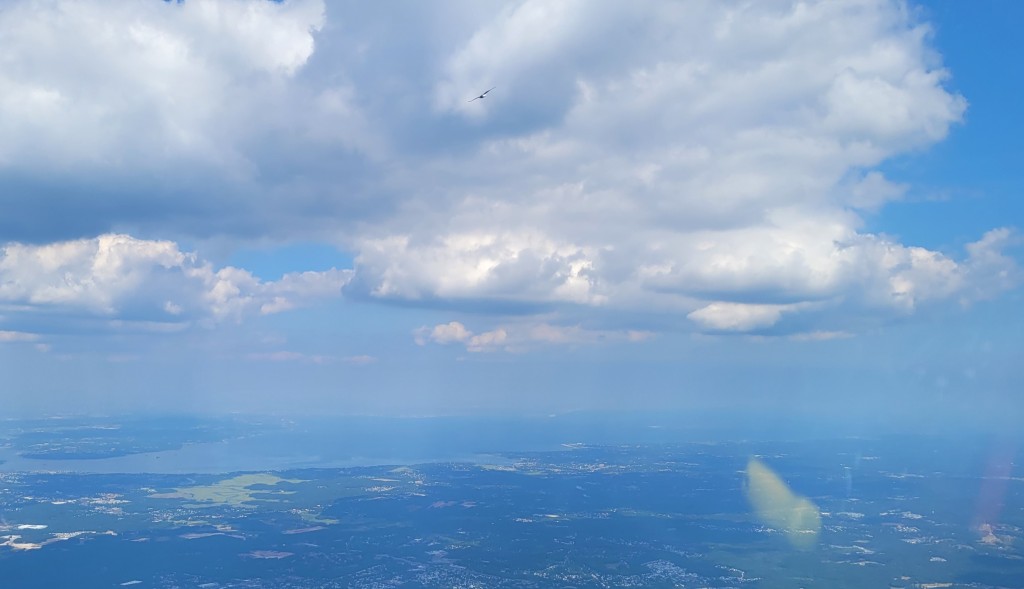

I had the most productive thermal soaring stretch I’ve ever experienced around here. Four flights, all exceeding 300 miles in distance achieved and averaging over five hours apiece. On the first I completed an out and return to Harris Hill, traversing the tricky high ground over the Poconos to transition toward the beautiful clouds beyond Scranton. One of the notable features of that flight was that the conditions were fairly heterogenous; there were pockets of good thermal activity and large stretches of blue in between. And by blue, I mean the totally dead and smooth kind of blue. I convinced myself that with a 50-1 ship that it should get across those challenging spots without too much difficulty, which worked out as intended.

In the following two flights, I worked the thermals forming along the northwest and southeast sides of the ridges for my first leg, followed by running east toward the coast and then back home for a long flight with a 300-400km triangle embedded within. The most exciting portions of these flights was flying in the vicinity of Philadelphia and Trenton, areas that typically are weak, wet, and dicey. Instead, I found some of the strongest and highest thermals in these areas, offering the ability to explore farther into New Jersey than I’d ever flown before. Maybe I could even venture to the Jersey shore? However, on both flights I ran into weakening conditions near Old Bridge as I crossed through the sea breeze front.

On the first instance, I barely escaped back to Princeton where I finally connected with lift that allowed me to complete a long and dead final glide under light drizzle. On the second, the sea breeze was pushed far inland due to the southerly winds. I found the step and a good single thermal, though it was not positioned satisfactorily relative to the surrounding airspace to take advantage of it as a lift line.

I had been fascinated by sea breeze fronts for a long time. I have seen them many times driving along the Jersey shore. It is defined by a line of blue, marine air paralleling the ocean, with a well defined line of cumulus clouds where the marine and warm and dry continental air collide. The clouds form a step, with the lower step forming a drooping curtain that looks like a waterfall. From the air, it looks like you are approaching the end of the four corners of the earth.

I’ve always wanted to experience flying along the front. It would be a lot of fun to soar along the long, defined edge. But there are several significant challenges that often preclude taking advantage of it. For one, the Jersey shore is a solid 50 miles away from Blairstown in the low and wet ground. This August is an exception to that rule and instead one could expect good soaring conditions in those areas. Secondly, the airspace is quite busy with extensive GA traffic. Thankfully Bill Thar installed a transponder in the Duckhawk, so this aspect was manageable. Thirdly and most importantly, the Jersey shore has complicated airspace. Bordered by the NY Class Bravo to the north and the McGuire MOA, several restricted zones, and the Atlantic City Charlie to the south, soaring the sea breeze would be no picnic. Further, the positioning of the front can move inland later in the day, which could create a situation where a pilot could head south early and then either run into airspace or fall out into the bad, marine side on the trip back north. These challenges had precluded my previous attempts to soar the breeze.

August 25th was when all the pieces finally came together. On this day, I just broke way from Blairstown and headed south first thing when I got up, regardless of the conditions setting up later. I took off at noon, settled into a thermal under the first cumulus cloud of the day along the ridge. Once at cloudbase, I could see the first clouds forming to the southeast near Hackettstown. I slowly floated out, taking every thermal, easing into the day. I had never left this early toward this direction before. It was exhilarating breaking from the standard mold of what we normally do and felt like I was flying at a completely different site!

My first solid thermal was near Round Valley reservoir and now I was established comfortably at 5,500ft. Nice looking cumulus clouds formed ahead and I picked up the pace. In what felt like no time at all, I was approaching Monmouth county and I saw the tell-tale signs of the sea breeze beckoning ahead.

Initially I downshifted and tried to get connected back to cloudbase again, though I was unable to find a solid climb. Initially, I followed the clouds all the way to the edge, right under the step. This did not work and I had to zig-zag back to the northwest when I finally connected with a solid thermal. What happened was I failed to recognize that the shape of the front created a wedge, with the apex of the wedge just under cloudbase and the marine air creeping in underneath. As I climbed, I drifted along the wedge up to the clouds, where I finally found consistent lift along the line.

As I headed south, I saw a flight of six fighter jets flying underneath in formation. Looking ahead, I was close to Lakehurst air force base and soon to enter the MOA. I tuned my radio to McGuire Approach, figuring that it was prudent and courteous to communicate with them. The radio was very active and I could hardly get a word in edgewise. When I announced McGuire Approach, Glider Four Six Three Two Papa, they got back to me and gave me a squawk code for my transponder. The controller asked me where I was heading and my intended altitude. I responded that I was heading toward Coyle Airport, an airport right on the edge of the following restricted zone and would fly between 5,500-6,500ft.

It was pretty nerve-wracking soaring the line. A little to the left and there was dead air. Off my right, there was restricted airspace. Ahead the airports were well in glide, though about ten miles apart. There was little room for error for if I started to drop it wouldn’t be easy to reconnect with the line. Finally I wanted to fly a bit more predictably for the benefit of the controllers; zig-zagging around like a crazed rabbit would cause me to be a burden and distraction to them. So I focused on the lift ahead, listened to the radio, and watched as C-130s took off underneath me.

The lift was mostly consistent, though not strong. I floated along at 60 knots, bumping along here and there. The best section was about 20 miles into the run, with a solid 6 knot thermal to 6,700ft along a solid wall of cloud. Ahead the breeze extended into restricted airspace and there was no obvious path on the continental side to extend around the back. So at Coyle Airport, 30 miles from where I started, I turned around and heading back north.

Coming back north was less stressful as I quickly attained comfortable glide back to terra firma in the form of Princeton Airport. I knew that even if I lost the line that I would make it back to soarable territory. The line lost some definition near Monmouth County, though persisted for 40 miles all the way to the New York Class Bravo. I flew right to the edge of the airspace, peering out into the haze in the distance. I could make out the skyscrapers, the Verrazano Bridge, and the whole profile of Staten Island. I had never seen the “Vee-Zee” as us New Yorkers call it from the Harbor side in a glider! I thought to myself that I could glide to my parents’ house from there.

Near Old Bridge Airport, I saw a speck at my altitude. Turned out it was an eagle, and I gladly turned into his thermal. As I went round and round, I saw the profile of the bird outlined against the whole city. Later I looked down and saw that he was flying with a friend! This pair of eagles climbed right through me. The brief thought to give them chase was dashed when I saw the eagles head straight toward Newark, into the Class Bravo airspace. Then I remembered that is what happens when you try to fly with creatures that are motorgliders and are exempt from ADS-B Out, Mode S transponders, altitude encoding altimeters, and even talking to the controllers! We parted ways and I headed west toward nice looking cumulus clouds near the Delaware river.

After a long glide, I got low enough to get a little grumpy and had to pay attention to landing options in the form of Van Sant airport and Doylestown as my outs. But as I crossed the river a little over 2000ft above, I saw yet another pair of eagles! I connected with a solid three knot thermal and rode up with these beautiful birds. I had several circles where one of the birds got very comfortable getting close to the Duckhawk, perhaps within several feet from my wingtip. It was surreal!

After the long climb, I looked over and saw that the high cloud cover off my shoulder to the left was arriving slower than expected. Ahead the clouds were high and well formed. This suggested that the day should last longer than forecast, so I kept heading west to extend my distance. After crossing the typical Kutztown hole, it seemed like the clouds were on steroids. A six knot thermal north of Hawk Mountain took me to 7,500ft. It looked like with the light winds there was some ridge-based convergence setting up in the area, creating bonkers lift. I ran the line just shy of Schuylkill County and headed along the edge of the ridges back toward Blairstown. The air felt marvelous!

Along the way, I enjoyed thermalling the Duckhawk. I finally felt like I had figured out how to thermal it. After extensive work to get the center of gravity in proper balance and seal ingthe canopy, I can thermal it shy of 50 knots in a solid 40-45 degree bank and 45 knots in a 35 degree bank and more flaps. Thermalling it is tricky because it gains energy so easily. You have to pull right on every gust and back it off just so when you fall off on the back side. After flying it for several hundred hours, I realized that I was doing this effortlessly and I was finally dialed into the glider.

After returning near to Blairstown, I climbed up to cloudbase and rode the last remaining bits of lift toward Dingman’s Ferry, completed my final glide in dead air and landed past 6 pm. I was very pleased to have notched another flight off my soaring bucket list; the New Jersey sea breeze has been conquered from Blairstown. This flight also doubled as my longest distance flown solely on thermals from my home site with 577km achieved on a six hour flight. Not bad during the so-called doldrums of August!

See my flight here.